When I first signed onto Jim Henson’s Creature Shop Challenge, I knew what I was getting myself into—or I thought I did. Reality shows are backbiting, bitchy little events that scream, “I’m here to win, not to make friends.” Part of me wanted to believe I was stepping into a world of creative camaraderie, but deep down, I knew better. What I couldn’t predict was how the pressure-cooker environment and the public’s perception would shadow us long after the cameras stopped rolling.

Reality TV may be unscripted, but it’s not unfiltered. Producers identify compelling personalities and then twist scenes, dialogues, and reaction shots into carefully constructed character arcs. You’re an artist one moment, villain the next. You’re likely more familiar with dating shows, but the selective framing producers use isn’t unique to them; it happens on skill-based series too. Shows like Face Off, Skin Wars, Ink Master, and even on Creature Shop deal with the same formulas.

I’ve seen that manipulation firsthand: footage that made fellow castmates out to look sloppy, insecure, or stupid was sewn into episodes to dramatize a downfall. The production gave no thought to how that would affect the artists in the real world.

That portrayal doesn’t stay in the studio. After airing, contestants often face seismic fallout—emotional, social, and financial. Some viewers register what they see on the screen as a person’s true colors. There is no consideration for creative editing, stress, or behind-the-scenes interference. And that’s by design. The viewer is meant to get lost in the narrative or program. They aren’t meant to analyze why an artist acted the way they did.

When we watch movies or scripted television, we know that is an actor on the screen playing a character. Love or hate the character, you know it’s an actor playing the role. But in the world of reality television, that word fosters the idea that the people on the screen are really like that. And the viewer is manipulated into believing it. The music, the edit, the angle of the shot transform the reality into a fictitious description based on real-world events. That’s a huge problem.

A 2024 survey found that 60% of the American public believes reality television has gone too far. They monetize participants’ pain and emotional well-being for entertainment. And viewers aren’t wrong. Shows like The Bachelorette, Love Island, The Swan, and even skill-based competitions have left behind contestants who suffer from anxiety, depression—or worse.

Now, many might say that we reality show participants knew what we were signing up for, and that’s true to a point. Think about it. How much stress, drama, or backlash would you have honestly expected from Jim Henson’s Creature Shop Challenge? It’s the Muppets. It’s Sesame Street. It’s fucking Fraggle Rock. But behind the scenes, it was anything but happy-go-lucky.

I recall arriving at the guest house, settling in, and the next morning getting a visit from the producers. The contract we signed was being amended, altered, or updated, depending on who you were talking to. You had little time to review it. There was no time to sleep on it. No time for lawyerly review. It was: sign this version or go home. Manipulation right out the gate.

And this sickly-looking producer asshole from across the pond saying that he would never put words in our mouths. I suppose they didn’t, but was what we said actually used in the proper context, or related to the actual conversation, or even the corresponding episode? That’s debatable.

When the real you is replaced with an edited-for-television version, what could really happen? A lot, actually. As I have stated, the fallout for reality show participants includes anxiety and depression, but also includes more suicides than you might imagine, and mental health professionals are calling it out.

Even viewers, including 56% of Americans, believe that reality show productions should be held responsible for contestants’ post-show mental well-being. But they continue to watch. Which is both unfortunate and fortunate at the same time. Weird, huh?

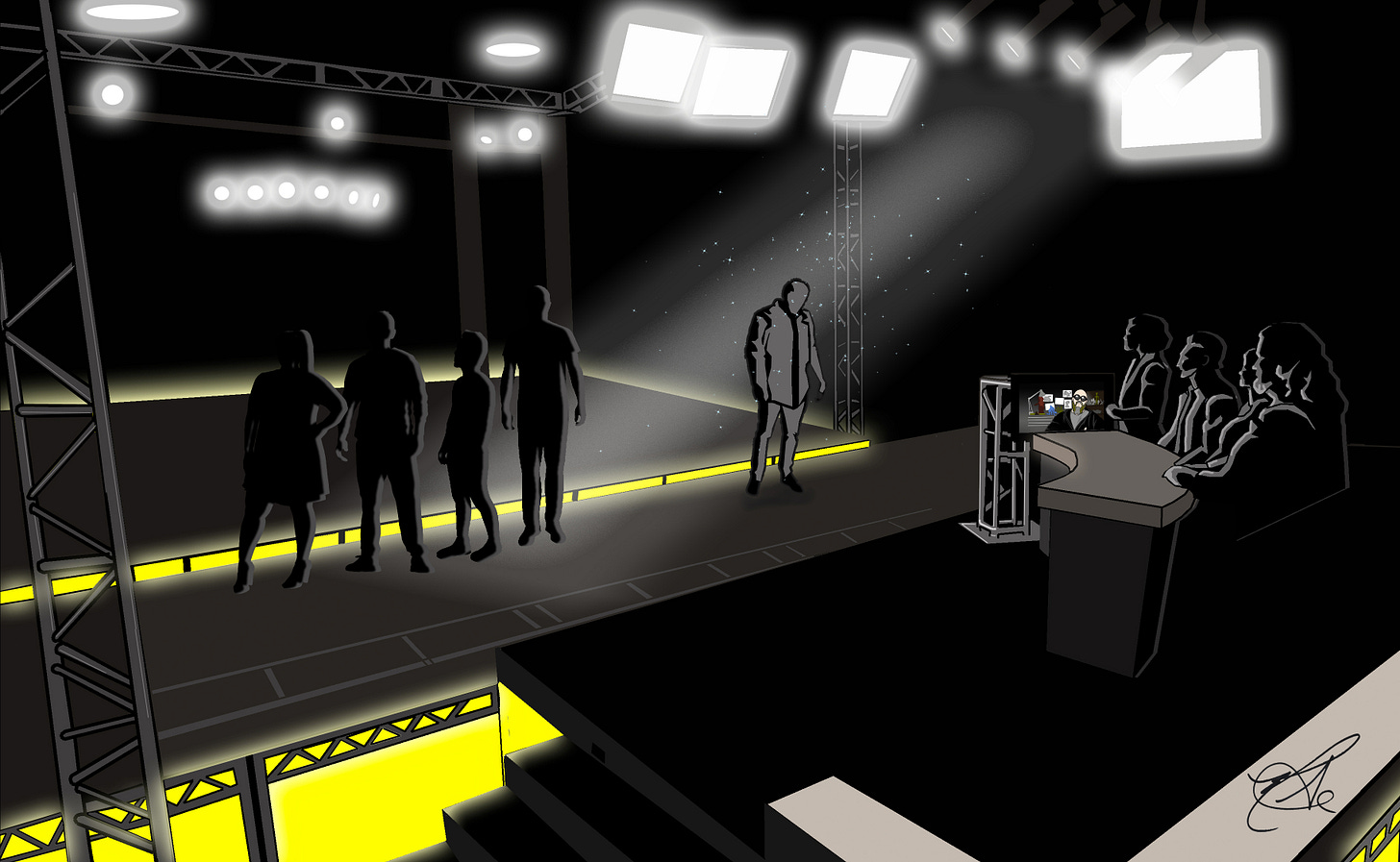

Skill-based reality shows don’t escape this scrutiny. Contestants on Face Off and Creature Shop Challenge were constantly critiqued under bright hot spotlights, judged on impossible deadlines—and then manipulated in editing booths to fit a dramatic arc. We’re human beings, not robots. But once you’re cast as “the cheater,” “the moron,” or “the loose cannon,” public opinion can become relentless even after the next episode airs.

I’ve seen brilliant artists who, because of producer edits, suddenly became unemployable. TV gains came at a steep cost: missed freelance opportunities, online harassment, and emotional isolation. A Face Off alum, discussing a post-show career, told me his bookings dried up overnight because clients had seen him portrayed as unreliable. And I’ve seen how skill-based shows mask this as part of “the game,” not the human consequence it is.

The truth is that when those human moments break out from behind the façade, it’s rarely just a person being an asshole for the sake of being an asshole. Teammate issues, tool failures, injuries, or even crew altercations most likely played their part in that human moment that got caught on camera.

As a cast member, you’re trying to be the best version of yourself, while sucking up the stress, surveillance, and injuries because the production is looking for any reason to make you look bad or send you home.

On one episode, I was using a huge grinding wheel. I was punchy because the machine was dangerous and the cameramen were distracting. I had a rare moment to use this equipment without the crew getting between me and the tool. But I saw a shadow in my peripheral and thought it was a cameraman. I panicked. I took my eyes off the grinder for a split second to look over my shoulder and took off the tip of my finger. This was an injury that could have gotten me sent home. I hid it from the casting team and the crew.

I cleaned the wound, superglued it, and covered it with gaff tape. The pain of the injury was something I personally buried along with the stress and indignities suffered on the production. And yes, it built up to a boiling point.

Mental health experts are increasingly recognizing the psychological fallout experienced by reality TV participants as comparable to trauma-related disorders. Some have even likened it to a form of situational PTSD. In high-pressure environments (particularly in shows that involve isolation, constant surveillance, and grueling schedules), contestants often face emotional breakdowns. Again, this is by design. You aren’t entertaining unless you are raw.

Studies focused on such environments have found that prolonged sleep deprivation, relentless camera presence, and manufactured stressors can erode a person’s mental resilience. What might feel like compelling, unscripted drama to the viewer is, in truth, a manufactured crucible that can leave lasting psychological scars.

From my own experience on a reality show, I can tell you there is no escaping those cameras or that microphone. You have no peace. You are constantly ON—meaning you aren’t able to drop the happy-go-lucky facade most of us show to our professional or social groups. In the real world, this lasts through the workday. But when you get home, you can shred the persona.

Imagine that. You can’t take a break. You can’t step away for a moment to just vent without a camera or microphone capturing it. You’re recorded at the studio, at the cast house, in the bathroom, everywhere. You have no space to just be… human. So yes, it’s traumatic.

Some progressive regulations are creeping in, like stricter duty-of-care rules in the UK and Australia—but of course, the U.S. industry lags. We still say fuck empathy for the sake of entertainment.

So what’s the fix for creators and reality TV contestants alike?

Show transparency in production: Editing disclaimers don’t protect us when employers and audience narratives are already fixed. There needs to be a team whose job it is to look out for the cast. The casting crew has divided loyalties, at least in my experience.

Post-show emotional support: Therapy, debriefing, and real access to crisis care after the cameras leave. I’d argue financial counseling as well. We put our professional life on hold when we do shows like these. When we come back, our finances are often in ruin. Contrary to popular belief, you don’t get paid for time on the show. You get a pathetic stipend of $300–400 for each week you’re on. For that, you’re in lockdown by the production for months. But that’s not all. The contract says the production owns your life story, likeness, and is entitled to a percentage of your future earnings. One might expect a bit more compensation for all that.

Acknowledge reality shows have human stakes and that there is a real toll to participation.

If you’ve ever watched a reality competition, it’s likely you haven’t considered the editing that just made good TV. That edit literally removes what actually happened and replaces it with a manipulation. And yes, it did make the story, but that wasn’t the whole story. That fabrication might follow the cast member home and affect them in ways you might never understand unless you lived it yourself. So, give us a break. Stop trolling the “villain.” Stop hating on the participants in social media posts. You don’t have the whole story, and you likely never will. I know—I lived it.

Eleven years after the finale episode aired and the professional, social, and financial aftermath still lingers in ways few viewers will ever understand.

I thought I knew what I was getting into—but what I really signed up for was a lesson in how easily the truth can be edited, sold, and forgotten. So, the next time you binge a reality show, ask yourself: are you watching a story, or someone’s real life being dismantled for your entertainment?

If you really want to know what life is like on a reality show, pick up a copy of Surviving Reality: This Is Not That Show. The book chronicles my experience on Syfy’s hit series, Jim Henson’s Creature Shop Challenge. You think you know reality TV, but the truth is, you don’t know the half of it.